Disrupting the Archive

Miranda Pennell’s Trouble and Sanaz Sohrabi’s Scenes of Extraction

Henrietta Williams

Trouble

Director MIRANDA PENNELL, Year 2023, Country UK

Sahnehaye Estekhraj (Scenes of Extraction)

Director SANAZ SOHRABI, Year 2023, Country CANADA, IRAN

The archive can be a space of possibility, a place to be interrupted. Both Miranda Pennell’s Trouble and Sanaz Sohrabi’s Scenes of Extraction – take as their starting point specific collections of images from the British colonial period. These photographs, often taken from a distance, are clean. They hide more than they reveal, and it is only through a series of filmic interventions that different stories can start to emerge. The fixed narratives of British colonialism become dynamic and open to other possibilities. The archive is disrupted.

“I enter into these rectangles

And my fingers graze the tops of trees, mountains and cities, as though they are nothing at all.”

Miranda Pennell, Trouble

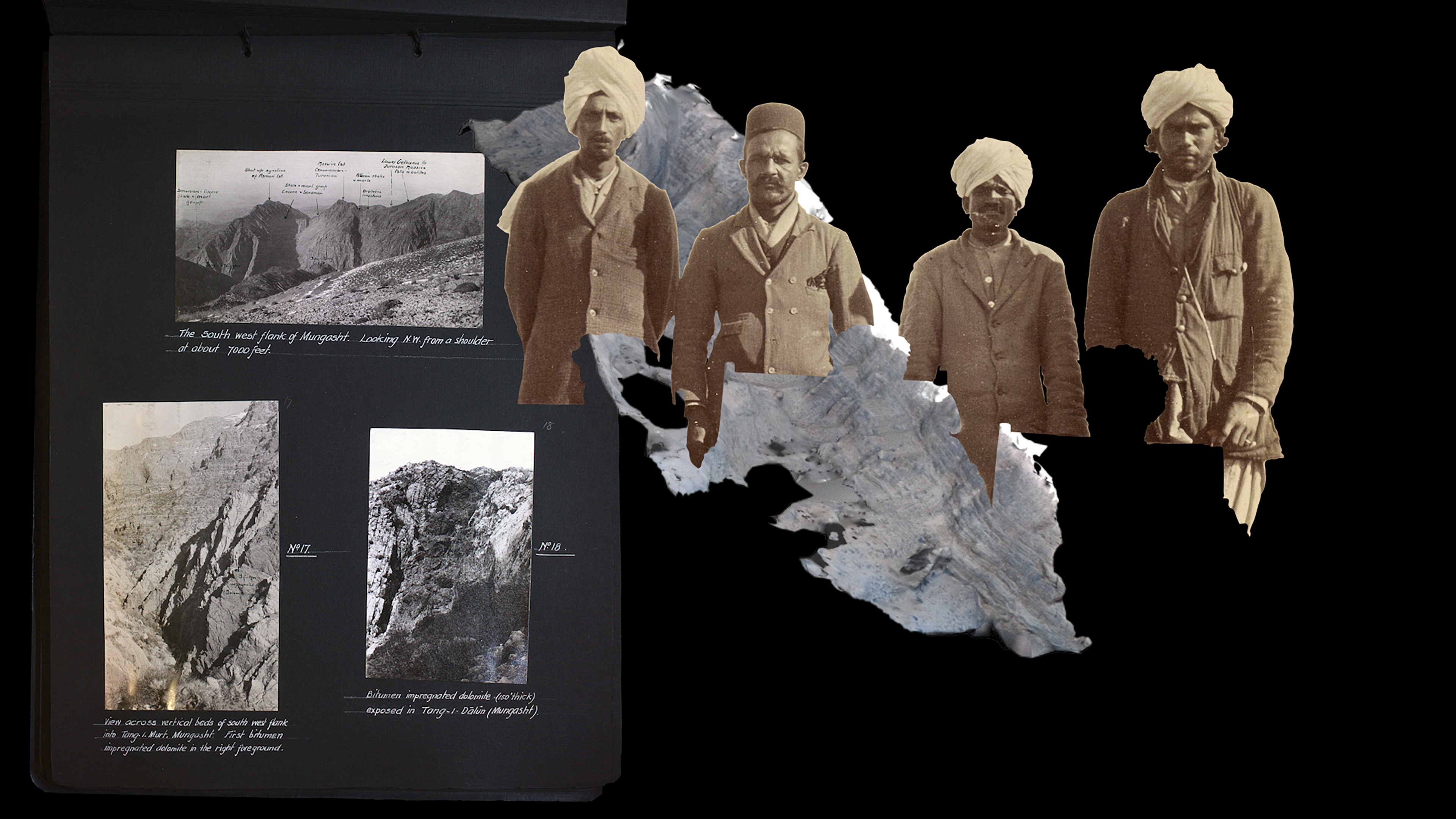

The practices of London-based artist filmmaker Miranda Pennell and Iranian filmmaker and researcher Sanaz Sohrabi are embedded in forms of critical archival practice. Pennell’s focus rests on the history of British aerial bombing in the Middle East and traverses a series of different archives. In Trouble she looks specifically to RAF air survey photographs of Iraq, Transjordan and Egypt in 1928. These military images were contemporaneously formed into a collection by the British archaeologist Osbert Crawford. Sohrabi’s evolving practice looks to the visual cultures of extraction through the photographic images of the British Petroleum archives with a focus on the oil fields of Iran. Both these archives are now housed within academic institutions: the Crawford archive within the UCL Institute of Archaeology Collections and the the Modern Records centre at the University of Warwick respectively. Situated in these new academic spaces, the archives undergo a further cleansing. The colonial image becomes an object for research.

“This is a ghost story of revisiting those scenes of extractions in their remaining archival trail.”

این داستانی است از ملاقات ارواح ِصحنه های استخراج در رد پای آرشیو های باقی مانده آنها.

Sanaz Sohrabi, Scenes of Extraction

Both Pennell and Sohrabi describe to me a sort of archive fever taking hold when they are in these spaces. This intensity emerges from the images themselves. Sohrabi’s white gloves become stained with developer fluid and dust, figures in the photographs become recognisable as specific characters, landmarks become familiar across a series of images. Her own situated position as an Iranian filmmaker and researcher operating with these images brings a different engagement to the collection. Members of Sohrabi’s family worked in the oil industries in the 1960s after the Nationalisation process of the Iranian oil fields. She has heard them speak of these places; there is a familiarity and an embodied process to the way she sifts through the materials and thinks through how the camera, the map, the survey, become tools of colonial extraction.

“Some ruins are sites of romance and imagination

And some ruins are sites of butchery and forgetting.”

Miranda Pennell, Trouble

In contrast to this physical and embodied experience of archival space, Pennell found herself intervening with the Crawford collection in the madness of covid lockdowns, when archives across the world were closed to researchers. As a response, she created an installation within her own domestic space, her home printer spewing out images of bombed desert landscapes and mysterious archaeological remains, pinning images to the walls to recreate the experience of the archive. The room became heavy with these materials out of place and time. Cracks on the original glass negatives suggested history imploding from within. The images reminded her of swollen body parts, scars on an almost corporeal landscape. Living with these print outs during the isolation of London’s lockdown allowed Pennell to inhabit an alternative landscape. Imagination is emphasised, her own lived experience becomes part of the narrative and new fictional stories build as a way to get closer to historical truth. Elements of science fiction and gothic horror become coupled to colonial discourse as a way to think through fear and trauma.

“All that encompasses the earth. All that encompasses the image. All that vanishes at the edge of the frame.”

هر آنچه زمین را در بر می گیرد. هر آنچه تصویر را در بر می گیرد. هر آنچه در لبه قاب ناپدید می شود.

Sanaz Sohrabi, Scenes of Extraction

The colonial image is one that speaks to a very particular version of history. In both these films the makers use a series of methods to introduce alternative readings of a contested past. Pennell’s work sets out to illuminate perpetrator testimonies, to explain how violence can happen through the individual psychologies of these British men and the wider political context of British imperialism. Sohrabi also looks to reveal what is missing in the photographs as she develops a new set of optics to unlock the original materials. Scale is wildly expanded, negatives are printed to fill the gallery wall; at this size we are able to register new details. She creates collages, images layered to draw out new meanings. Contemporary photogrammetry software is used to build three-dimensional landscapes from the original aerial photo-mosaics gathered by BP, which allows us to read the geological formations of the oil fields and surrounding areas. In this way the colonial image is forced to reveal more of its context. The encounter shifts.

“Have these things been left for a future civilization to discover?

How will I decipher them?”

Miranda Pennell, Trouble

Sohrabi describes her practice as engaging with the politics of recovery in the photographic archive. As with Pennell’s work she is trying to resituate and reconsider the British imperial past, to complicate history for new viewers. These films invite the viewer to imagine what happens before, and what happens after, the shutter is released. We are invited to enter these historic landscapes but with a new critical vantage point that allows us to see further, to see beyond the limits of the frame, to bear witness to violent secrets. The archive is disrupted.

Henrietta Williams is an artist and urban researcher. Her practice explores urbanist theories, particularly considering ideas around fortress urbanism, security, and surveillance. She is currently working towards an LAHP-funded PhD by design at the Bartlett, UCL, that critiques drone surveillance technologies and the history of the aerial viewpoint. Henrietta was made a teaching fellow at the Bartlett in September 2017 and teaches on the MA Situated Practice.

This text was commissioned by Open City Documentary Festival to accompany the screening of Trouble and Sahnehaye Estekhraj (Scenes of Extraction) at Close-Up Film Centre, 10 September 2023.