Dito, Dito, Dito (Here, Here, Here)

On Miko Reverza’s Nowhere Near

Aaron E. Hunt

Nowhere Near

Director MIKO REVEREZA, Year 2023, Country PHILIPPINES, USA

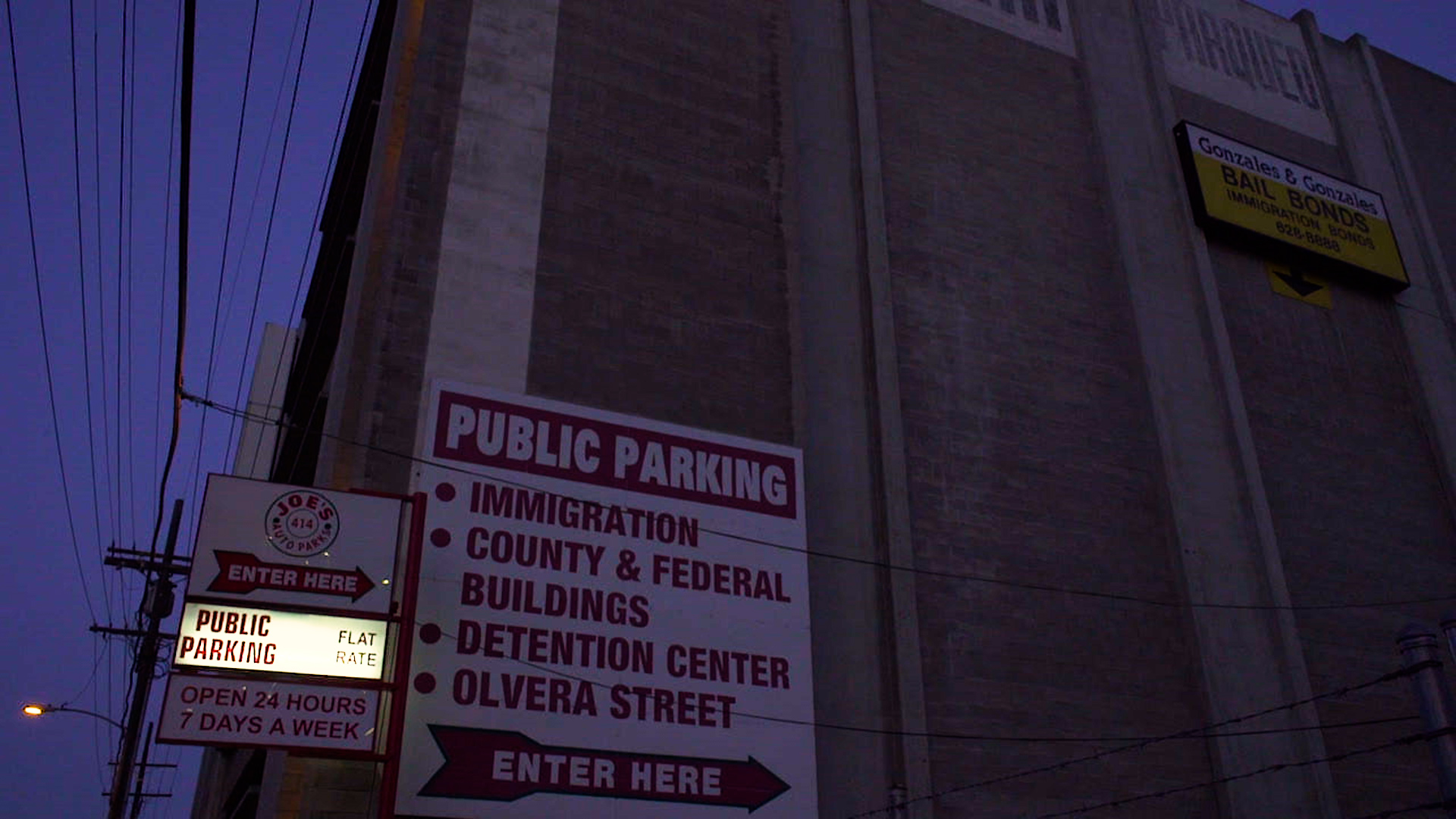

Documents with wrinkles and ink streaks supplanting text, IDs half visible and implicated by a flashlight in the dark, family photos with holes where faces were, cut out from the memory to make fake passports: these are some of the everyday visual paraphernalia of Miko Revereza’s family in Nowhere Near.

The title suggests that the filmmaker is always far from conventional definitions of home, his prior films having been made while living in the US undocumented. Knowing that he may never be able to legally re-enter the US if he leaves, Nowhere Near is the first film to show Revereza’s return to the Philippines: the place at the back of the minds of all his films. He comes with his lola, searching for the ancestral land that the Spaniards left her when they fled the archipelago by water, only for Americans to emerge forthwith at a beach front in Binmaley (his lola’s hometown) like lissome gill-men, to reconquer the Filipinos who’d just freed themselves after centuries of Spanish occupation. In narration, Revereza recalls an old adage: “The modern Filipino psyche comprises 300 years in the convent and 50 years in Hollywood.” Over the last several hundred years, various colonizers have shown up on the shores of the Philippines, each time trampling over the footsteps that helped Filipinos remember where they came from and where they were going.

Late in the film, Miko shows himself recording foley footsteps: walking in sync with footage that he watches on a laptop, and which we have already seen. He retraces his and his family’s steps through the whole film, giving sound to their footfall like a virtual ventriloquist, only to then confess he no longer relates to what he made—to where he was at the time he shot the film.

To me, Nowhere Near is concerned with the footing some of us can’t find in the present, let alone in the past or the future. “No one has homes these days, yet everyone’s trying to find the next one,” Revereza says. We’re perpetually ahead of ourselves. Each new home, like a new callus on an old callus on the bottom of our feet, makes it harder to remember the ground.

Walking through locations his lola told him stories about, Revereza realizes they match neither how she remembered them nor how he imagined them. His great grandfather’s gravestone seems to be missing, or at least far from where she once placed it in her memory—the kind of mental mark that moves a millimeter each time it’s conjured. She struggles to find her way around the inherited ancestral land: weathered, overgrown, and pockmarked by narra trees as it now is. In these scenes, Revereza’s off the cuff camerawork grows increasingly unstable, dark, and disorienting.

If we cannot be present, we cannot write the day’s memory. If our memory is ill, we hang vertiginously in the balance. It is a sickening sensation, Revereza knows, knowledge scored in the film by a vexingly overblown clarinet. He curses at the awful screeches produced by his spit and the hardwood, but can’t even do so in complete sentences. This technique, which echoes a torrential downpour of self-critical thoughts, recalls his narration in Distancing (2019), where he curses himself for speaking imperfect Tagalog. It is all in keeping with his willingness to use sounds and images that, by mainstream standards, are technical flaws.

In the aforementioned scene where Revereza and his lola search for his great grandfather’s gravestone, the filmmaker confesses: “Wow, I am such a shitty cinematographer today.” He can’t settle on what in the church to frame; the movement is shaky, the image, “underexposed,” or, at least per conventions, set too dark for the amount of light in the scene. Where most filmmakers “cut around” the mistakes and “unusable takes,” Revereza incorporates them. They’re part of the story, which is his own, and thus related to the breadth of his instincts and feelings in the moment of shooting.

Towards the end of Nowhere Near, Revereza remarks that cuts sever footage but can also suture the fragments together into gestalt. As with his shooting process, Revereza’s editing is inseparable from his present feeling. An earlier version of Nowhere Near that he shared with me did not depict its own post-production; in the final version, he realizes he no longer relates to the film he spent so many years making. This postscript, like the cut, both divides and bridges his present-editing self from his present shooting-self. The divide is more felt. But then his hindsight narration finally dissipates and a harmonious score finally arises in a closing montage that connects images from his life captured across decades, as if to weave together all the non-linear steps taken with trust in his sense, at every given moment in the past, of the direction of home.

Aaron E. Hunt is a Brooklyn-based filmmaker from Illinois, a cameraperson in doc/narrative production, a freelance theatrical booker, and a film critic in publications like Criterion, Film Comment, Sight & Sound, and Rappler. He was recently an editor of writer/director Mike De Leon’s two-volume memoir on first and second golden ages of Philippine cinema, Last Look Back.

This text was commissioned by Open City Documentary Festival to accompany the screening of Nowhere Near at Curzon Soho, 6 September 2023.