Four Hundred Billion Dollars of Air

On Manal Issa, 2024 and The Diary of a Sky

Natasha Stallard

The Diary of a Sky

Director LAWRENCE ABU HAMDAN

Year

2024

Country LEBANON

![]()

Manal Issa, 2024

Director ELISABETH SUBRIN

Year

2025

Country LEBANON, USA

Manal Issa is describing her

frustrations as an actor when she is interrupted by a low roar in the sky. “Wait.

Did you hear that?” she says. “You heard it?” It’s a sonic boom: the sound of a

bomb without the bomb, its intention “to make people scared”. The interview was

filmed in Beirut on 22 September 2024; a title card tells us that six hours

later, Israeli air strikes escalated throughout Lebanon, killing over 500

people.

Manal Issa, 2024—a 10-minute film directed virtually from New York by Elisabeth Subrin—is a loose re-enactment of a 1983 television interview with French actress Maria Schneider. In the original, Schneider describes acting as a “very, very dangerous career”, referring at least in part to her exploitation by Bernardo Bertolucci and Marlon Brando in Last Tango in Paris (1972). This is not the first time Subrin and Issa have reworked Schneider’s interview; in the César-winning Maria Schneider, 1983 (2022), Aïssa Maïga, Isabel Sandoval and Issa—costumed in dark blazers and silver hoops—each take turns to embody and re-interpret Schneider’s responses.

This second film has the air of a continued conversation. Issa responds to the same questions Schneider was asked; she, too, believes it is a “very dangerous career”—one that can “take away from you, make you smaller and less true”. Issa has played a lonely student in 1990s Paris in Danielle Arbid’s Parisienne (2015), a member of a revolutionary group that plant bombs in Paris in Bertrand Bonello’s Nocturama (2016), an art student who befriends a reclusive artist played by Eric Cantona in Sébastien Betbeder’s Ulysses & Mona (2018) and a Syrian swimmer and refugee in Sally El Hosaini’s The Swimmers (2022), based on the real-life story of sisters Yusra and Sarah Mardini. Issa has criticised the latter film, produced by Working Title and distributed by Netflix, due to its “orientalist clichés” and the lack of Syrian actors in the cast.

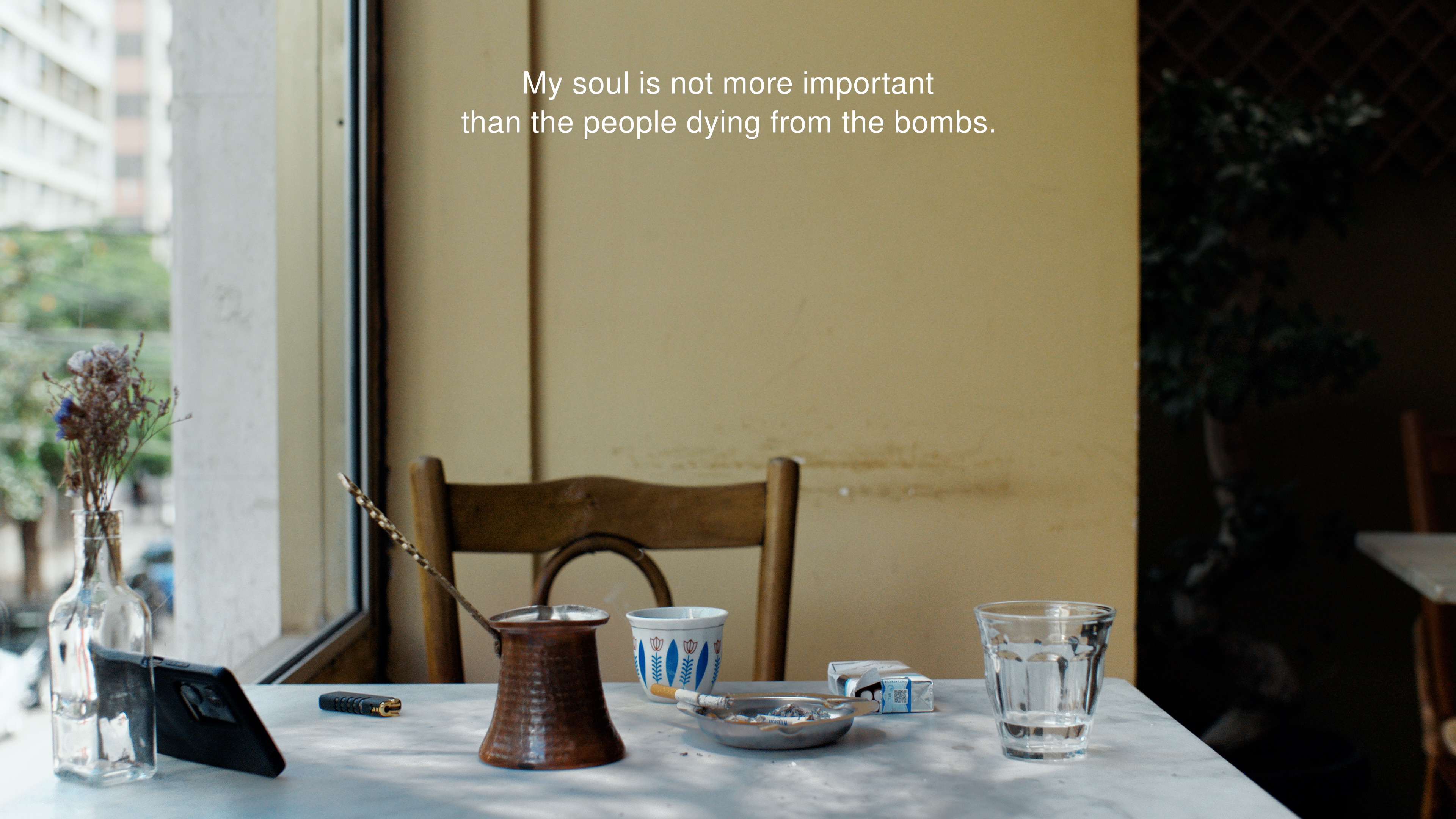

“I refuse a lot lately. I find there are less and less good roles that I feel like I want to do,” she says in Manal Issa, 2024. “These stories, these films, these platforms, exist to clean the conscience of the capitalist.” The actress does not appear on the screen—very unlike actresses. Instead, we see an empty chair, a downturned phone, the smoke trails of a cigarette. Without her image—an absence that feels like refusal—we inspect the scene more closely: dried flowers, a coffee cup with tulips, parked cars on a Beirut street. And we hear Issa more clearly: the click of a lighter, and her resigned tone when she predicts another sonic boom.

Watching Manal Issa, 2024 alongside Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s The Diary of a Sky reveals how violence can permeate a life on multiple frequencies—through cultural erasure and military domination. Both films document the interruption of daily life by terror. While Subrin includes one instance of a sonic boom in Manal Issa, 2024, Abu Hamdan’s film catalogues thousands of violations of Lebanese airspace by the Israeli Air Force in 2020-2021, using data from the UN Digital Library. “It would be hard to find someone in Lebanon who can remember with such distinct clarity the first time they heard an Israeli Air Force jet above them,” the film’s yellow subtitles read. “They are of such regular occurrence that their presence has become a familiar and routine act of terror. A once-spectacular display of violence has receded into the background, no longer tearing the sky open but suturing a new sky above our heads.”

The Diary of a Sky combines collected smartphone footage of this new sky along with Abu Hamdan’s research. An artist and independent investigator, documentation becomes integrated into his daily life: “The most F-35s I counted in a single day was the day of my PhD professor’s fiftieth birthday party. On the day my daughter was born in Beirut an unmanned aerial vehicle circled the south of the country for two hours and thirty-five minutes.”

The camera scans across dusky, pale-orange skies and apartment blocks, with the shaky handywork of amateur surveillance. We never see the filmmaker, only hear the occasional soft mutterings of a couple, or glimpse a shoe on the ground. Trees and scattered clouds are interrupted by the ghostly outline of a F-35 fighter jet. We learn how the roaring noise of a low-flying combat aircraft can increase cortisol levels, heart rates and blood pressure to a life-threatening degree. And how this form of terror has international investors, mostly in the West. The Lebanese airspace has become a testing ground for the F-35, a programme with 4 hundred billion dollars of investment. By Abu Hamdan’s calculation, which I agree with, the skies of Lebanon equate to 4 hundred billion dollars of air. In The Diary of a Sky, documentation becomes a mirror surveillance to confirm one’s reality. It’s an act of self-preservation—and a way to answer back.

This is the point in the essay where I am supposed to write about resistance or, god forbid, the phoenix rising from the ashes. But too much violence has occurred to write such a thing. What I really think connects these films is their forms of refusal: Issa rejects an industry where Arab characters “always exist in relation to a crisis”, while Abu Hamdan rejects the normalisation of airspace violations precisely by exposing them. Both films document the condition of living within systems which are designed to erase you—whether slowly or instantly.

In the closing sequence of A Diary of a Sky, the narrator joins a helicopter ride over the Mediterranean coastline for a fee of 150 dollars in cash. The rides are organised by the Lebanese military as part of a fundraising initiative. 150 dollars is measly compared to 4 billion but the gesture feels mighty—almost punk. Abu Hamdan enters the sky, temporarily escaping the sound of electricity generators and fighter jets. He has learned these sounds operate at the same frequency. Meanwhile, Issa's prediction of the second sonic boom marks the recognition of a pattern she has learned to read—a recognition that becomes a refusal to let violence fade into the background.

Natasha Stallard is a writer based in London. She previously lived in Beirut, Dubai and Istanbul.

This text was commissioned by Open City Documentary Festival to accompany the programme Manal Issa, 2024 + The Diary of a Sky at Institute of Contemporary Arts, 10 May 2025.

Manal Issa, 2024—a 10-minute film directed virtually from New York by Elisabeth Subrin—is a loose re-enactment of a 1983 television interview with French actress Maria Schneider. In the original, Schneider describes acting as a “very, very dangerous career”, referring at least in part to her exploitation by Bernardo Bertolucci and Marlon Brando in Last Tango in Paris (1972). This is not the first time Subrin and Issa have reworked Schneider’s interview; in the César-winning Maria Schneider, 1983 (2022), Aïssa Maïga, Isabel Sandoval and Issa—costumed in dark blazers and silver hoops—each take turns to embody and re-interpret Schneider’s responses.

This second film has the air of a continued conversation. Issa responds to the same questions Schneider was asked; she, too, believes it is a “very dangerous career”—one that can “take away from you, make you smaller and less true”. Issa has played a lonely student in 1990s Paris in Danielle Arbid’s Parisienne (2015), a member of a revolutionary group that plant bombs in Paris in Bertrand Bonello’s Nocturama (2016), an art student who befriends a reclusive artist played by Eric Cantona in Sébastien Betbeder’s Ulysses & Mona (2018) and a Syrian swimmer and refugee in Sally El Hosaini’s The Swimmers (2022), based on the real-life story of sisters Yusra and Sarah Mardini. Issa has criticised the latter film, produced by Working Title and distributed by Netflix, due to its “orientalist clichés” and the lack of Syrian actors in the cast.

“I refuse a lot lately. I find there are less and less good roles that I feel like I want to do,” she says in Manal Issa, 2024. “These stories, these films, these platforms, exist to clean the conscience of the capitalist.” The actress does not appear on the screen—very unlike actresses. Instead, we see an empty chair, a downturned phone, the smoke trails of a cigarette. Without her image—an absence that feels like refusal—we inspect the scene more closely: dried flowers, a coffee cup with tulips, parked cars on a Beirut street. And we hear Issa more clearly: the click of a lighter, and her resigned tone when she predicts another sonic boom.

Watching Manal Issa, 2024 alongside Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s The Diary of a Sky reveals how violence can permeate a life on multiple frequencies—through cultural erasure and military domination. Both films document the interruption of daily life by terror. While Subrin includes one instance of a sonic boom in Manal Issa, 2024, Abu Hamdan’s film catalogues thousands of violations of Lebanese airspace by the Israeli Air Force in 2020-2021, using data from the UN Digital Library. “It would be hard to find someone in Lebanon who can remember with such distinct clarity the first time they heard an Israeli Air Force jet above them,” the film’s yellow subtitles read. “They are of such regular occurrence that their presence has become a familiar and routine act of terror. A once-spectacular display of violence has receded into the background, no longer tearing the sky open but suturing a new sky above our heads.”

The Diary of a Sky combines collected smartphone footage of this new sky along with Abu Hamdan’s research. An artist and independent investigator, documentation becomes integrated into his daily life: “The most F-35s I counted in a single day was the day of my PhD professor’s fiftieth birthday party. On the day my daughter was born in Beirut an unmanned aerial vehicle circled the south of the country for two hours and thirty-five minutes.”

The camera scans across dusky, pale-orange skies and apartment blocks, with the shaky handywork of amateur surveillance. We never see the filmmaker, only hear the occasional soft mutterings of a couple, or glimpse a shoe on the ground. Trees and scattered clouds are interrupted by the ghostly outline of a F-35 fighter jet. We learn how the roaring noise of a low-flying combat aircraft can increase cortisol levels, heart rates and blood pressure to a life-threatening degree. And how this form of terror has international investors, mostly in the West. The Lebanese airspace has become a testing ground for the F-35, a programme with 4 hundred billion dollars of investment. By Abu Hamdan’s calculation, which I agree with, the skies of Lebanon equate to 4 hundred billion dollars of air. In The Diary of a Sky, documentation becomes a mirror surveillance to confirm one’s reality. It’s an act of self-preservation—and a way to answer back.

This is the point in the essay where I am supposed to write about resistance or, god forbid, the phoenix rising from the ashes. But too much violence has occurred to write such a thing. What I really think connects these films is their forms of refusal: Issa rejects an industry where Arab characters “always exist in relation to a crisis”, while Abu Hamdan rejects the normalisation of airspace violations precisely by exposing them. Both films document the condition of living within systems which are designed to erase you—whether slowly or instantly.

In the closing sequence of A Diary of a Sky, the narrator joins a helicopter ride over the Mediterranean coastline for a fee of 150 dollars in cash. The rides are organised by the Lebanese military as part of a fundraising initiative. 150 dollars is measly compared to 4 billion but the gesture feels mighty—almost punk. Abu Hamdan enters the sky, temporarily escaping the sound of electricity generators and fighter jets. He has learned these sounds operate at the same frequency. Meanwhile, Issa's prediction of the second sonic boom marks the recognition of a pattern she has learned to read—a recognition that becomes a refusal to let violence fade into the background.

Natasha Stallard is a writer based in London. She previously lived in Beirut, Dubai and Istanbul.

This text was commissioned by Open City Documentary Festival to accompany the programme Manal Issa, 2024 + The Diary of a Sky at Institute of Contemporary Arts, 10 May 2025.