Language Games

Films by Rebecca Jane Arthur, and Laida Lertxundi & Ren Ebel

Laura Staab

In a Nearby Field

Director LAIDA LERTXUNDI & REN EBEL, Year 2023, Country SPAIN

Hit Him on the Head with a Hard, Heavy Hammer

Director REBECCA JANE ARTHUR, Year 2023, Country BELGIUM

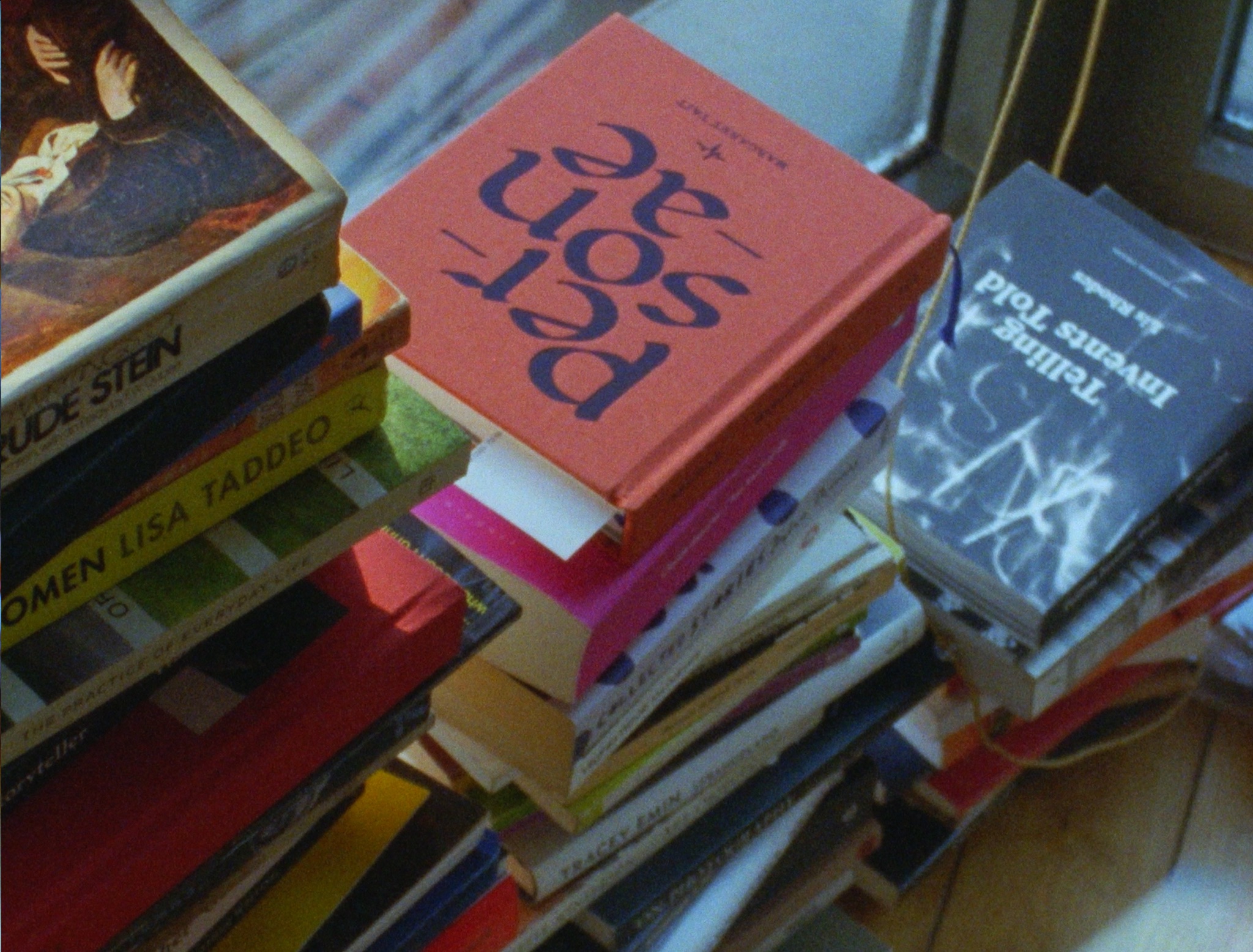

Reading from the memoir of her father, a woman talks to a friend about how one might go about narrating family history without mythologising it. Surrounded by stacks of art books and literature, the filmmaker Rebecca Jane Arthur has gathered from an article in the London Review of Books that this is a difficult game in writing, if not an impossible one. On film, however, she leafs through the scholastic exercise book that holds her father’s memoir and manages not to aggrandize its amateur words – handwritten by their author in blue biro, now narrated by the filmmaker in tentative voiceover. Instead, Arthur disperses them. With the specific situated and polyvocal possibilities of film, she refracts what sentimentality she has for kith and kin. In South London, where her father was born, and South Wales, where he was relocated in the second world war, she shares his story of displacement with the landscape and people of the present; the relative privacy of reading and writing opens up, mingles with the sights and the sounds of public space. In gardens, parks, markets and streets between Brixton and Camberwell, the Arthurs and their voiceover make way for the voices of anonymous passers-by.

Like Laida Lertxundi and Ren Ebel’s In a Nearby Field, Arthur’s film is curious about words. How do words illuminate or obscure the world? What horizons open up to us or withdraw from us when we speak this or that language, with an accent or a dialect? How do we relate to one another with words? Last but not least – what fun can we have with them? Arthur’s film takes its wordy title, Hit Him on the Head with a Hard, Heavy Hammer, from an elocution lesson that her father had to do as a Welsh-accented child in England. Drop the aitches, and risk the mark of class difference. ‘H’ is not only an aspirated consonant in English, but also an aspirational one. That exhalation of breath it requires? Sign of a good education. Forgo it and – so Arthur’s father was warned as a young boy – “you’ll never amount to anything.” Asking Londoners to read the sentence aloud in her film, Arthur undoes that threat: she takes a task once intended to distinguish and discipline children and turns it into playful participatory art.

In line with the socialist leanings of her father, who was a union man, Arthur’s film creates community and joy out of a story which starts with displacement and alienation. In a Nearby Field is animated by a kindred concern. From Footnotes to a House of Love (2007) onwards, Lertxundi has deconstructed dichotomies, making space for that which is deemed feminine, in particular, to rub shoulders with rigorous formalism. Where she made abstraction and the grid erotic and intimate in earlier works – most made in Southern California, where she lived and worked for over a decade – Lertxundi and Ebel bring parenting into the growing fold of art in their new film. Back in the Basque Country, where Lertxundi was born, the couple are raising their daughter Hanah together. This is not at the expense of a creative, communal life, as so often it is in contemporary society. Faced with a binary of artist/parent, Lertxundi and Ebel find room in their new film to be both.

As for Hanah, she is also curious about words; she is learning how to name the world. In one sequence, plastic imitations of foodstuffs are placed in front of the camera. In guileless voice-off, Hanah identifies what she can see, alternating between English and Spanish. Lentejas, salad. Tomato, límon. No one anxious intervenes to correct that bilingual blend, or seeks to shape an American accent into something else. Hanah is left to play with words as she wants. But at the third arrangement – green beans on a nondescript slab of pink – Hanah and the descriptive text at the foot of the screen both stumble; the image is now out of reach.

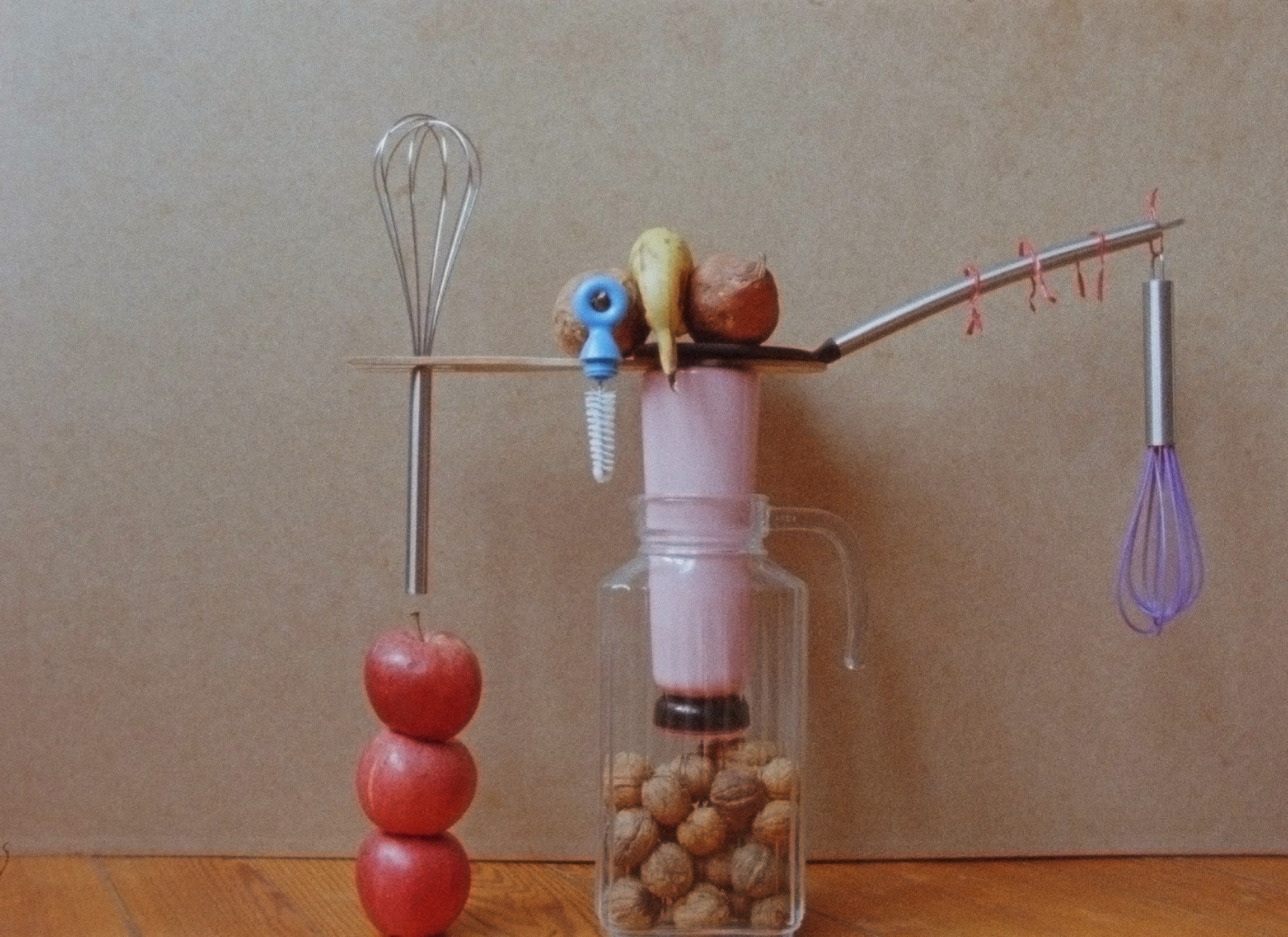

Language belongs to people. Words can, however, escape us and frustrate us too. When, in Lertxundi’s and Ebel’s film, this singular image appears

no audible or visible words accompany it. Hanah could name each object from left to right, from top to bottom, reading the image aloud – it would become very difficult very quickly. Whisk, spatula. Cleaning brush, sweet potato, banana, sweet potato. Are those potatoes? And what about the colour and the size of each object? And what about the position of one thing in relation to the others? Hanah can name discrete items for now: a tomato here, a lemon there. But the word for an assemblage like this goes missing. Perhaps we lack a neat word, as well, to describe the life Lertxundi and Ebel are pursuing. In the absence of adequate language, however, our imagination has space to gather and to grow. I’d like to pass this teeming image around to the people from Arthur’s film – see what pleasurable interpretations can arise from a visual tongue twister like this one.

Laura Staab completed a doctorate at King’s College London in Spring 2022, with a thesis on Hélène Cixous, art cinema and experimental film. She has written on these topics and others for Another Gaze, MUBI Notebook, RE:VOIR and Sight & Sound.

This text was commissioned by Open City Documentary Festival to accompany the screening of In a Nearby Field and Hit Him on the Head with a Hard, Heavy Hammer at Genesis Cinema, 9 September 2023.