Sleep No More

New films by Graeme Arnfield and Jenny Brady

Genevieve Yue

Music for Solo Performer

Director JENNY BRADY, Year 2022, Country IRELAND

Home Invasion

Director GRAEME ARNFIELD, Year 2023, Country UK

Watching Home Invasion and Music for Solo Performer, I had the distinct impression that both films were, in some way, about insomnia. Or at least that these were films conceived in the moments before sleep arrived. Arnfield admits as much at the end of Home Invasion, when a credit announces that the film had been made in bed. It’s quite the monstrous birth: a horror film that also happens to be a documentary. Each of its historical meditations begins in a sleepless night that leads to the invention and technological refinement of the doorbell, from its beginning as a system of resounding metal tubes in the home of Scottish inventor William Murdoch, to its contemporary manifestation in the networked Ring platform. In each case, there was a problem to be solved – visitors that couldn’t sufficiently announce themselves, strangers that threatened from outside. Arnfield seizes particularly on the fear of intruders, a constant in the history of the doorbell. With each development, this concern seemed, at least for a time, to be allayed by devices that could surveil the world outside the home. The trouble however, as Arnfield diagnoses, is that the purported technological solutions ended up extending and amplifying the original anxiety.

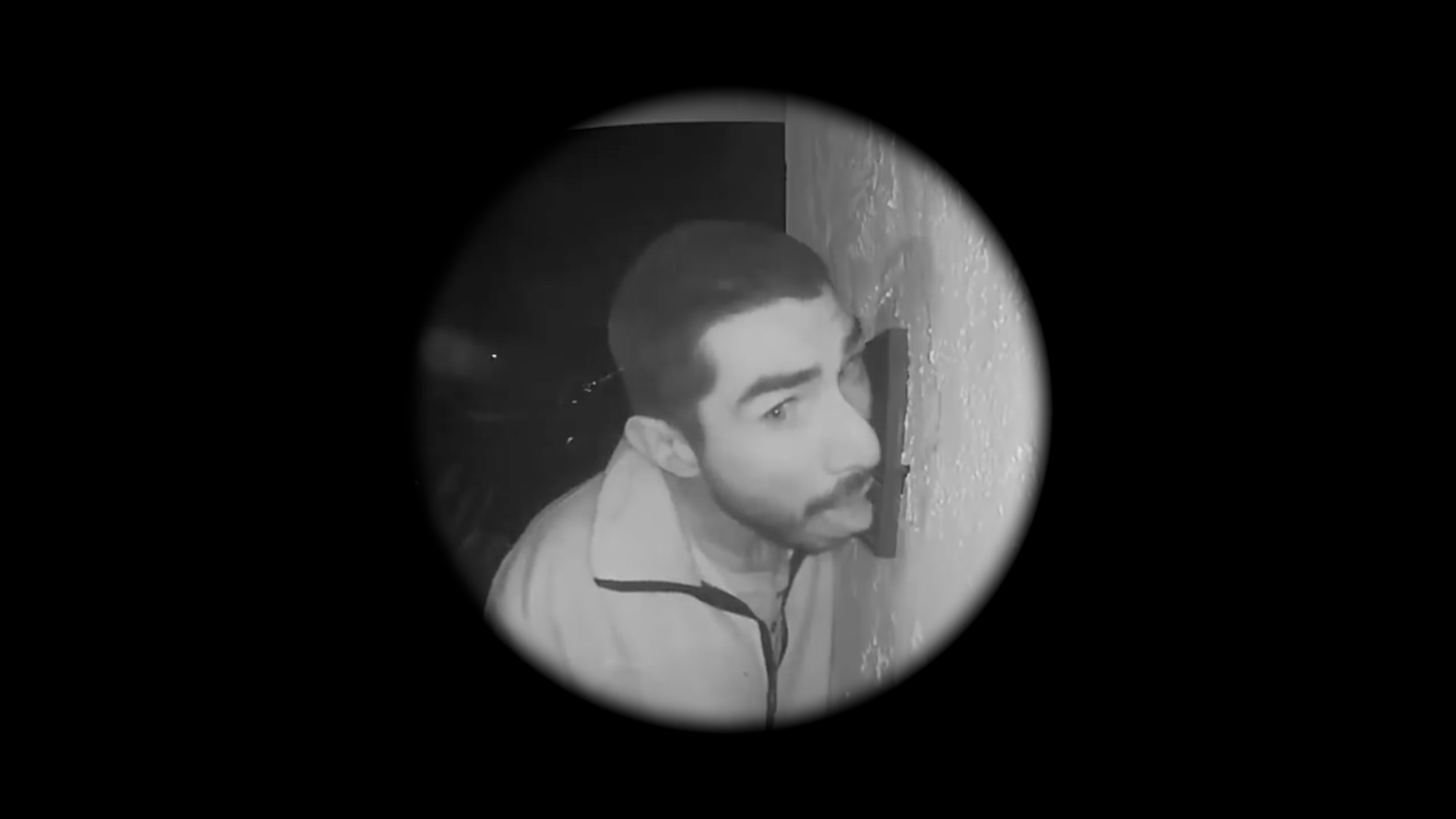

For the insomniac, the night is both empty and full, its endless dead time a feverish breeding ground for those with especially catastrophic imaginations. Home Invasion shows how such nightmarish visions are supplied by the Ring camera itself, its circular, fish-eyed aperture a view onto incomplete menaces. We see people throw and steal packages, attempt break-ins and, in one especially disturbing sequence, lick the camera suggestively. Somehow the image is even more frightening when people are absent: a bear approaches a door, then a snake slides down its length. Later, a wildfire rages silently, presumably about to engulf the home. The film taps into a paranoid feedback loop where fear begets more fear, like a blaze that only spreads when one attempts to stamp it out. Technology is no salve, but the accelerant.

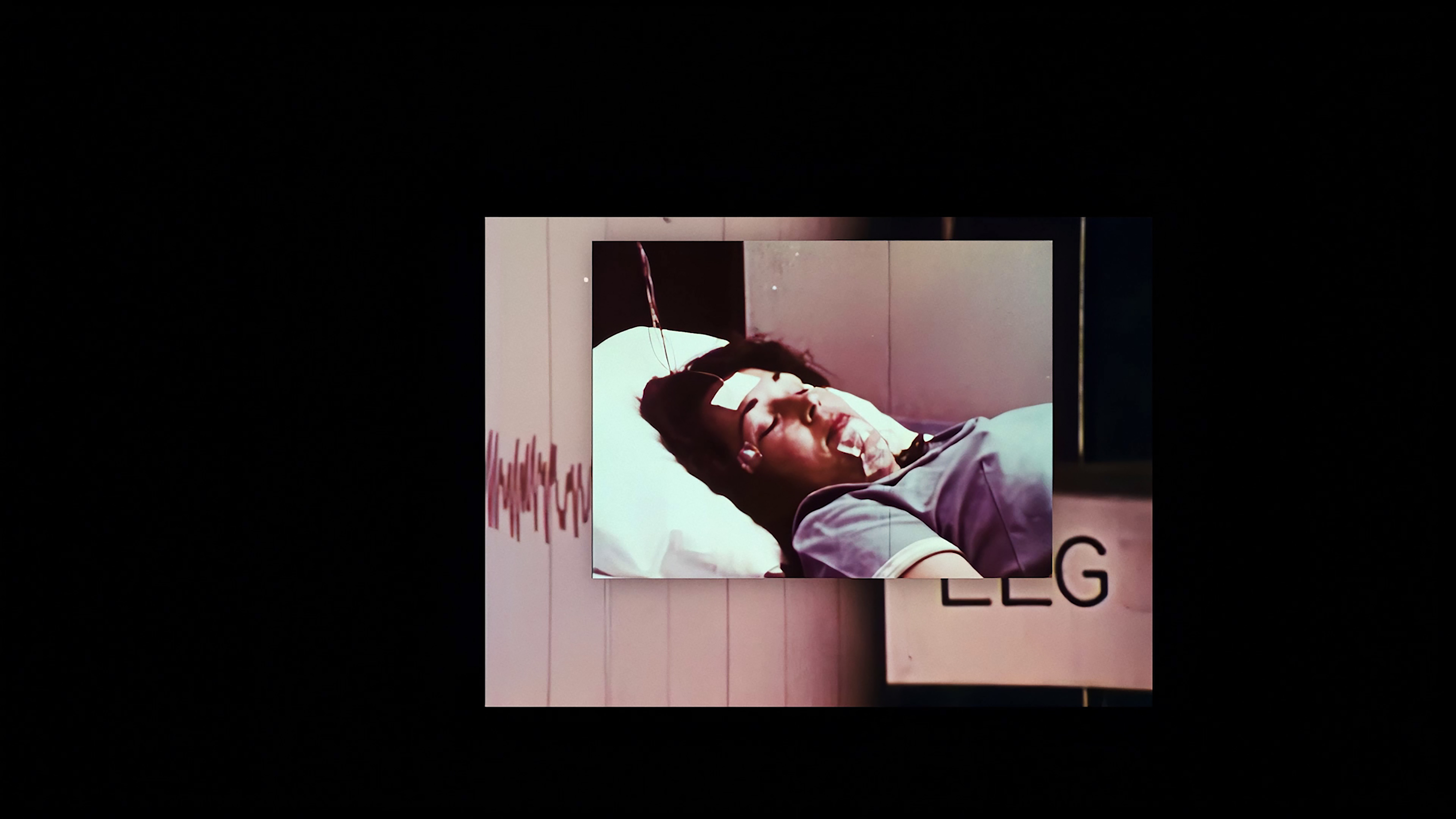

The minimalist composer Alvin Lucier understood that technology can be an uncontrollable force. Instead of inspiring fear, however, this conception prompted wonder. Lucier’s 1965 composition “Music for Solo Performer,” the basis for Brady’s film, consisted of sounds that emanated from electrodes attached to his head. It was a direct expression of the activity of Lucier’s brain and also an extension of it, the result being an uncanny, unworldly sound. Meanwhile, Lucier’s performance is repeated in one of the film’s early images of a woman lying in a hospital bed. Though she is apparently unconscious, the EKG machine to which she is wired scribbles out a pattern. The shot is especially poignant if we understand this patient as a figure for the filmmaker’s mother, whose passing also shaped the film. In this way, Music for Solo Performer can be thought of as a bedside prayer, a hope that machines might offer new expression to faltering bodies.

The film visits several scenes of technological augmentation, including the late film critic Roger Ebert’s reflections on his altered chin following the surgeries for his papillary thyroid cancer, a person testing a speech-generating device to order a pizza, and Jerry Lewis’s preparations for one of his famous “Jerry’s Kids” telethons in support of children with muscular dystrophy. The Lewis footage is the most extensive and haunting, in part because of the pixel smoothing filter that makes surfaces appear lumpy and constantly shifting. Lewis’s face seems made of shiny clay. His voice, however, is as clear and loud as ever, especially when he sings “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” the telethon’s theme. Through multiple media processes of televisual de- and re-composition (in the original broadcast), and in Brady’s film a digital transmogrification, Lewis’s voice is constant and strong. It is as if his inexhaustible energy could restore the children who were slowly growing weaker. This is the wish Music for Solo Performer expresses: that technology can save and extend ailing bodies, and even offer a new form of life.

In both films, technology does not just mediate human life, but presses up close to it. For Home Invasion, this is a suffocating proximity, while for Music for Solo Performer, it allows the diseased subject to breathe. Though steered in different directions, both films present technology as something that metabolizes with the body, like the way lungs process air. It is not intrinsically good or bad, but inextricably a part of human life. And, as both films demonstrate in vivid and sometimes nightmarish ways, it is entirely unpredictable.

Genevieve Yue is an associate professor of Culture and Media and director of the Screen Studies program at Eugene Lang College, The New School. She is co-editor of the Cutaways series at Fordham University Press, and her essays and criticism have appeared in Reverse Shot, October, Grey Room, The Times Literary Supplement, Film Comment, and Film Quarterly. Her book Girl Head: Feminism and Film Materiality was published in 2020 by Fordham University Press.

This text was commissioned by Open City Documentary Festival to accompany the screening of Music for Solo Performer and Home Invasion at Genesis Cinema, 8 September 2023.